ATORKOR’ THE TOWN OF SLAVES

Atorkor is a small village in the Anlo District of the Volta Region (South Eastern) part of Ghana. It is located on the Atlantic coast with beautiful sandy beach.

Atorkor is located some 28 kilometers away from Keta, a prominent coastal town in the Volta Region of Ghana. Due to its proximity to the Gulf of Guinea, the area is very sandy and there is little arable land available for farming and the greater portion of the area is covered by sea sand.

Atorkor village is blessed with lovely natural beaches, calm & peaceful life, good roads linking it and Accra, the capital city of Ghana as well as surrounding towns and villages. It is sandwiched between the sea and the lagoon, and has some of the warmest and friendliest people in all of Africa. Basically, it is a safe, enchanting village and a wonderful place to visit. It has a population of about 6,000 people.

There are no major economic activities in the village. The main occupation of the village is fishing for which the inhabitants depend on the sea and the Lagoon. Fishing in Atorkor has declined considerably due to:

Depleting stocks in the immediate vicinity of the shoreline and the use of archaic traditional fishing methods which limits the fishermen to fishing only in the immediate vicinity of the shoreline.

Overfishing as well as illegal fishing by large foreign fishing trawlers.

The construction of the Dam by the Ghana Government to generate Electricity which resulted in the Lagoon/River virtually drying up.

ORIGIN OF THE NAME ATORKOR

The original name of the village was Adelako’s hamlet (“Adelako kope”).

Adelako was one of the sons of Togbui Tsatsu Adeladza 1, the second Awoamefia of Anlo. Adelako erected hamlets for hunting& fishing purposes at the spot we now call Atorkor, hence the name Adelako’s Hamlet. During that time, River Volta had suitable tributary flowing from Anyanui to Keta lagoon and thus very suitable for navigation. The hamlet was erected at the bank of the flowing river and it became an attractive trading spot.

The spot brought in Akan speaking traders who transacted business with the natives. However, due to the swarm of mosquitoes, the traders demanded in the Akan language “metor mekor ntem” meaning “let’s buy and leave quickly”. This Akan saying had changed the original name of Adelako’s hamlet to Atorkor, a corrupted version of “metor mekor ntem”.

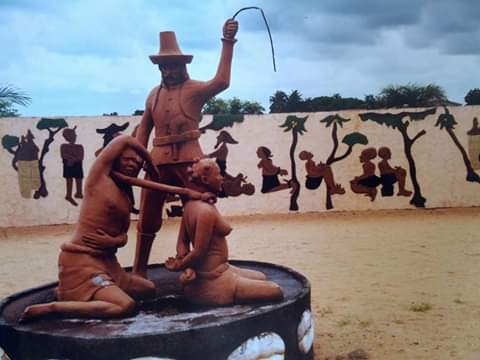

ATORKOR AND THE SLAVE TRADE

Atorkor like many other places in West Africa was associated with the slave trade. Atorkor was part of what was formally known as the Upper Slave Coast. Because of its location on the Atlantic Coast it became a port for the shipment of captives procured from the interior.

BEGINNING OF SLAVE TRADE.

The Trans-AtlanticSource: Koenzagh.com | Michael Kwadzo Ahiaku ( Photojournalist). Slave Trade And Ghana

Ghanaians, it seems, view the Trans-Atlantic slave trade as an unfortunate historical human calamity which must not be allowed to happen again.

But the question is how many Ghanaians are truly aware of the role people living within that part of the continent at the time played in the actual act of capturing and selling their own people in return for things such as gunpowder and kola? The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and Ghana, an exhibition mounted as an attempt to educate the public on the historical occurrence of the slave trade, is currently on at the National Museum in Accra.

Not only is there evidence of some 35 slave markets dotted around the area in West Africa where Ghana is situated, but there are also many routes, transit camps and objects available to establish that the trade took place under horrendous conditions. Several of these transit camps and markets have been identified within the area where Ghana is currently situated. And some of these inland sites are characterized by water cisterns, remnants of slave warehouses, rock boulders and trees with large or long exposed roots for chaining the enslaved. Burial grounds for slaves, and their ancestors, as well as their masters, are still visible at places like Salaga,

Saakpuli and Kafaba in the Northern part of Ghana. Other places include Assin Manso and Effutu in the Central Region area, and Atorkor, Peki Dzake and Adafianu in Anloland.

The forts and castles which started as European trading posts later becoming dungeons and slave auction areas which dot along the coast of Ghana even till today, don’t give the whole picture.

This exhibition tackles the story of the slave trade from another more important angle which has, hitherto, not been told much. It tells how deeply African chiefs and kings themselves were involved in the trading, ordering raids and kidnaping, and arranged markets where the captured were sold. Toward the end of the 17th century and in the first few decades of the 18th, slave raiding and kidnaping became the major occupation among the Akwamu, Akyem, Kwahu, Krepi, and Fante in the southern part of the Gold Coast and among all the major ethnic groups in the northern part of the country. It tells how those captured had to walk several kilometers under brutal conditions. Chained to each other with neck to hands iron shackles, they only got to rest at transit camps before arriving at the markets. Their

new masters would then distinguished them from each other by marking them with branding irons which were put in fire to become red hot before they were stamped on specific parts of their body.

Many of the original iron shackles, some specially made for children, and the branding irons with inscriptions like ITA and GHC are in this exhibition. Also on display are recent color photographs of many of the transit camps and markets as they look today.

A brass cannon of English make from Sekondi, and an original 18-century flute lock musket (gun) can also be found. But of all these items on display, the one that struck me the most was a collage made by an inmate of the Accra Psychiatric Hospital, depicting chiefs and their subjects at a meeting with Europeans at the Christianborg Castle. One wonders if it is not his effort in trying to comprehend how such an atrocious and de-humanizing act can be meted out to fellow human beings, that got this person insane.

Slavery and slave trading is an age-old institution practiced on almost every continent in this world. People sell people for many different reasons. It is not so rampant these days, but it still takes place. The Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, however, was the most organized, and it profited its European and African counterparts a great deal. The people of the Gold Coast were not mere spectators of this misadventure but active participants. The Portuguese were the first to introduce Atlantic trade into Ghana, trading in consumer goods but later resorted to slaves to be used as the labour force in the new world in America. By this time the British, French, Dutch,

Danes and Germans also joined in the scramble for African humans, at prices even cheaper than horses!

In 1889, a German traveler called Blinger visited the Salaga market in the northern part of Ghana today and made this startling revelation. “300 cowries are sold for a male slave, 400 for a female slave, 1000 cowries for a horse, 500 for an ox, and 150 on a sheep.” That was the depth to which African human lives were reduced.

It is estimated that from 1451 to 1870 between 10 and 12 million slaves were exported from Africa. Between 1620 and 1870, over half a million slaves from Africa were sent to the mainland of America. From 1733 to 1807, the Gold coast supplied 13.3% of slaves needed by South Carolina. Between 1710 and 1769, 16% of what was needed for Virginia. In the total English trade, Ghana supplied 18.4% between 1690 and 1807. For the whole of the 18th Century, the Gold Coast supplied 12.1% of the total Atlantic trade (Perbi 1995).

The exhibition is a small but powerful one that will provoke any viewers senses on how and why the slave trade actually took place. Telling the story of how African themselves were the kingpins who captured and sold off their own people adds a relevant piece to the jigsaw of this ‘historical human calamity’. It conveys an important message of acknowledgment and reconciliation. It makes sense of the history lessons about the slave trade. It is more powerful than any movie ever made

about the subject, and should be a ‘Must-See’ for, especially, every school child in this country.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and Ghana are on till December 15 at the National Museum, Accra.

This is mainly a historical and political discussion of the slave-trade history in Anlo (Ghana) from the 17th to the 20th century (with the focus on the 19th to the 20th century).

The author opens with a discussion of different attitudes of slave descents in West Africa and North America towards their origins and further discusses that in modern Ghana, few Ghanaian historians have worked systematically on slavery and the slave trade.

Two developments brought about more discussion of the legacy of the slave trade and slavery in the Anlo society in Ghana today: the first development came from UNESCO’s declaration of some forts and castles in Ghana built by the Europeans, among which Atorkor, an Anlo coastal town, and former slave-history site was also listed; the second development was a result of a report in 1993 by Ghanaian media about the existence of ritual female bondage in some areas in Ghana.

Anlo, located in southeast Ghana, bordered to the east by the Republic of Togoland and isolated from the rest of Ghana, lacked gold and ivory as well as land and fertile soil, all of which made it both necessary and accessible to play a part in the slave trade.

Before the colonial period of Anlo, it had been from the 1750s on constantly engaged in dispossessing its neighbor Ada’s salt ponds and fishing grounds, which Anlo lacked itself. The consolidation of the Anlo war-machinery also contributed to Anlo’s being an important player in the slave trade.

The Dutch took charge on the Slave Coast from the 1630s, and were joined in the Guinea trade from the mid-seventeenth century by the English, French, Swedes, Brandenburgers and Danes. By the late 17th century, several polities dotted between the Volta estuary (south) and the Lagos Channel (north) all took part and vied as intermediaries in the Atlantic slave-trade. Part of the reason was geographical: the major Anlo slave marts were all located between the lagoon and the sea, facilitating the smuggling of slaves along the lagoon and the shipping from ports other than Keta, which was mostly under Danish control.

Not only did the slave traders in Anlo sell slaves to the New World, they also kept some slaves themselves, especially women, whom they married and over whom they had much control (including their offspring).

The slave trade was welcomed by the local governor, who at the same time also felt threatened by the wealth of the slave traders. From the 18th century, the priests of powerful shrines began to demand young women, fiasidi, as payment from devotees who sought their service and these women remained as servants of the shrine for the rest of their lives. These services could be in aid of childbirth, healing, the settling of disputes or vengeance for wrongs committed. Fiasidibecame institutionalized and grew in Anlo society over the 19th century.

fiasidi loosely means “wife of chief” and mainly exists in Anlo (north), whereas the other kind of human payment, trokosi (literally means “pledge of god”) is mainly practiced in Tongo (south).

A trokosi currently functions as a punitive institution for checking crime. However, the exploitation of the sexuality and labor of the trokosi are its most blatant features.

From the 1970s on, humanists in Ghana as well as in other countries began investigating the trokosi practice and condemned it as inhumane, which brought international attention.

The author believes that it is the acts of betrayal by local chiefs that contributed greatly in the abduction of local inhabitants, and that it is the chiefs that suggested these slave-trade spots be considered as a Slave-Trade Memorial worthy of national preservation and tourism promotion. It is also those powerful chiefs, indigenous priests and educated “traditionalists” that pledged to uphold African “culture” in the face of Western/ Christian encroachment.

In the process of investigating into the slave-trade history of Anlo, the author discovers that despite the fact that the “oral tradition” of the slave-trade is passed down through generations in forms of songs, drum names or as proverbs, the “oral data” of individuals get lost quite easily, and usually dies with the death of the individual who experienced them.

DEDICATION OF THE ATORKOR SLAVE MEMORIAL

(The Anlo Traditional Council of Chiefs)

Atorkor is a small settlement in the Anlo area of the Volta Region of Ghana, or what was formerly known as the Upper Slave Coast.

As fate will have it, the pressure for African captives was to have drawn this sleepy village into the midst of the events of the Middle Passage. The preoccupation was to avoid being made captive by European slavers who were known to make raids in unsuspecting coastal villages, or from raids by more powerful neighbors.

No thanks to its cove in that rough part of the Atlantic coast of boiling water, Atorkor became a port for the shipment of captives procured from the interior. The Danes were the main buyers of slaves in that part of the Slave Coast. However, in 1792, the Danes abolished the slave trade and ban it to its nationals in 1803.

Britain was to join later in 1807. Both nations took steps to stop the slave trade in the Gold Coast and the Upper Slave Coast. By 1860, the trade-in slaves has stopped effectively in the Upper Slave Coast and people started returning to more humane means of sustaining themselves and their families. So did the people of Atorkor.

That is why they suspected very little danger when some boats [2 or 3?] docked at the port of Atorkor and they were invited in to drum to entertain the apparent friendly traders. Little did they know that the boats were Brazilian slave boats out to trick them into slavery.

The Brazilians, Portuguese and the Spaniards were adamant in their refusal to stop the slave trade, and shifted their activities to the Lower Slave Coast centered around the port of Whyddah.

Many Brazilians, Portuguese, and mulattoes who had settled along the coast continued to organize the slave trade. The last slave boat was known to have left the Slave Coast in 1888. But then, no one was expecting a slave boat even before that time at Atorkor!

Hundreds of men and women, therefore, entered the boats to perform the new dance of Buteni to these white men. Before anyone realized it, anchors were secretly lifted and the boats started sailing to the open sea. Scores jumped into the ocean in an attempt to escape what was obvious to all: captivity.

Those who could not swim drowned and were swept ashore by the powerful waves of the Atlantic. Many unfortunate ones were carried away into captivity never to be heard of again. Both the dead and the captives left behind hundreds of little children who went into a collective shock and long mourning.

These little orphans had to be taken care of by relations and the general public in other towns. By 1960, there were old people still alive who were the children of those stolen people. Relations from towns such as Anloga, the traditional capital of the Anlos, continued to send food to them. As the world focus attention on the captives of the Middle Passage, we must not forget Atorkor, the innocent victim of man’s greed and inhumanity.

By: Michael Kwadzo Ahiaku ( Photojournalist).